Court Martial (Episode 15)

The name Mankiewicz means you're Hollywood royalty. But it doesn't mean you can write Star Trek.

An undated photo of screenwriter Don Mankiewicz. Image source: StarTrek.com.

Write What You Know

Courtroom dramas have been a television staple since the 1940s. Shows such as They Stand Accused, Divorce Court, Perry Mason, and The Defenders were quite familiar to American TV viewers.

They also appealed to studios and networks because they were affordable to produce. The same courtroom set was used in each episode.

It’s no surprise, then, that Don Mankiewicz pitched a courtroom drama to Gene Roddenberry.

Because Star Trek was about a futuristic space navy descended from today’s military, it only made sense that this courtroom drama would be a court martial.

That would appeal just fine to Roddenberry. His last series, The Lieutenant, had been about a US Marine Corps rifle platoon leader. Several episodes involved a court martial as part of the plot.

Mankiewicz was related to at least five other writers. His grandfather, Frank M. Mankiewicz, wrote texts about German language and philosophy. His father, Herman Mankiewicz, was a screenwriter. Herman cowrote the script for Citizen Kane with Orson Welles; the two won an Academy Award for best screenplay. His uncle Joseph won four Academy Awards as writer/director for A Letter to Three Wives and All About Eve. His brother Frank was a White House correspondent who went on to be the campaign press secretary for the doomed Robert F. Kennedy during the 1968 Democratic presidential primaries. Don’s son John is a producer and writer, with credits such as House and the US version of House of Cards.

The 1955 film “Trial” was based on a novel written by Don Mankiewicz, who also wrote the screenplay. Video source: Warner Bros. Classics YouTube channel.

At age 32, Mankiewicz in 1954 wrote a courtroom drama called Trial that won him the Harper Prize. The novel was turned into a screenplay, which he also wrote. In 1959 he and co-writer Nelson Gidding received an Academy Award nomination for I Want to Live!

Don became a prolific TV writer, with credits for such anthologies as Studio One, Ford Television Theatre, Playhouse 90, and Kraft Theatre. He wrote courtroom dramas for The Joseph Cotton Show: On Trial. In 1965, while Star Trek was still in its larval stage, he wrote an episode for The Trials of O’Brien, a short-lived series about a Shakespeare-quoting attorney played by Peter Falk.

Mankiewicz had little experience with speculative fiction. He’d written six episodes for One Step Beyond, an anthology series about supernatural events. Not exactly boldly going.

The 1959 episode “Epilogue” of “One Step Beyond” was the first of six written for the series by Don Mankiewicz over its three-season run. Video source: PizzaFlix YouTube channel.

That didn’t deter Roddenberry who, as we’ve discussed in earlier columns, had pitched his show to members of the Writers Guild of America. According to Marc Cushman writing in These Are The Voyages: Season One, Don lived in Long Island, New York but happened to be in Los Angeles when Gene showed his second pilot “Where No Man Has Gone Before” to potential script writers.1 Attaching the Mankiewicz name to Star Trek must have been all too tempting for Roddenberry.

Cushman quoted Mankiewicz as saying Roddenberry needed “something that could be done very cheaply.” He suggested a courtroom episode.

He wanted to put James T. Kirk on trial.

Upon Further Review

Because the story took place in the future, Mankiewicz suggested that the damning testimony come not from people but from a computer.

The Enterprise computer would be called the Information Reception and Retrieval Unit (IRRU). That didn’t stick (thank goodness). The IRRU would be a co-conspirator, resenting Kirk so much that it would lie about the circumstances.

Keep in mind that, as with the other free-lance writers, Mankiewicz was flying blind. None of them had a clue what a Star Trek story looked like. All they had for references were Roddenberry’s March 1964 sixteen-page outline “Star Trek Is … and the two pilots. As they wrote and submitted story outlines in the spring of 1966, it became clear to Gene that his screenwriters needed more direction. He issued a memo to them clarifying his vision for the Star Trek universe.

Don’s experience was no different. His first outline was submitted on May 3. Unauthorized Roddenberry biographer Joel Engel quoted from a memo Gene sent to Don dated May 6 chastising the writer for failing to grasp the show’s concept.2

Not leaning on you, Don, but want you to see the direction in which the sum of all these things would be taking “Star Trek” as a series.

By August, Gene was still displeased with the Mankiewicz project. Typical of his concern is this six-page August 15, 1966 memo from Roddenberry to producer Gene Coon, who’d joined the show one week earlier on August 8. Coon was still learning the Star Trek universe himself, so the memo discusses not only Roddenberry’s concerns but also educates Coon about the show’s concept and characters. On page one, for example, Roddenberry calls out Mankiewicz for referring to helmsman Sulu as “Sumo” but also explains to Coon who Sulu is and what he does.

This paragraph has an interesting comment about the Enterprise chain of command. Fans have been known to debate who is in charge if both Kirk and Spock are not on the bridge. Roddenberry wrote:

In Spock’s absence, there would be someone at or near Kirk’s chair who is in command. This could be Sulu if Sulu has been temporarily replaced with an acting helmsman.

So who’s next in line? Whomever Kirk or Spock choose. It could be Sulu. It could be Scott. It could be Uhura, although that might have been too much for 1960s network television.

We discussed in “Miri” the departure of Grace Lee Whitney from the show. An “executive” (the evidence suggests but does not prove it was Roddenberry) sexually assaulted Grace after filming on August 26, eleven days after the August 15 memo. Grace was notified after the episode that her seven-episode contract would not be extended. “Miri” was her sixth episode; a cameo in “Conscience of the King” was the seventh and final appearance.

In the August 15 memo, Roddenberry debates if Rand should be in the episode and, if so, what the character’s role should be. Gene certainly would have been aware of the seven-episode commitment and been counting how many times Whitney had been used. At this point, perhaps he intended to extend her contract. We’ll never know.

The memo concludes:

Not a bad first draft, considering Mankiewicz’s unfamiliarity with the direction of the show. Seems to me he could have read our writer-director memo a little more carefully, or perhaps we should take a hard look at it ourselves and revise it since important aspects of our format did not seem to get through. At any rate, am convinced Don could do an excellent job on a rewrite if we aim him in the proper direction.

Don’s final draft was submitted on September 6. He added the idea of tracking heartbeats aboard the Enterprise to prove that Finney was still alive. According to Cushman, Rand was still in the script at this point; the Desilu Business Affairs memo terminating Whitney’s contract would be issued on September 8.

Cushman wrote that Mankiewicz left the project at this point because of “marital difficulties.” Coon turned over the script to Steve Carabatsos, who had also joined the production staff in early August. Carabatsos simplified the script, slimming it down as well as deleting the Rand character.

After one final polish by Coon, the script went to Star Trek’s NBC minder, Stan Robertson. He complained that “this is probably one of the most ‘cerebral’ scripts that we have received to date.” Robertson wanted more physical action, typical of the network’s complaints. But it was too late to change the script, with shooting scheduled to begin on October 3.

Lights, Camera, Think

In his narrative history of the episode, Marc Cushman detailed the difficulties producing it, quoting director Marc Daniels:

While we were making “Court Martial” we all felt, “Oh God, this is a dog, let’s get it over with as best we can …” Part of the problem was that it didn’t have much action in it.

Was it a woofer? Let’s watch the episode and decide for ourselves.

The episode opens with the Enterprise in orbit around a planet. Starbase 11 is located here. (In early drafts, it was Starbase 811.) The starship requires repairs after surviving an ion storm.3

The starships in port for repairs at Starbase 11.

In Commodore Stone’s office, we see a wall chart listing the various starships in dock for maintenance. Their names are not listed but their registry numbers are. (One is NCC-1700, meaning at least one Constitution Class ship was built before Enterprise — the Constitution, presumably.)

Stone and Kirk discuss the loss of Lieutenant Commander Ben Finney. Kirk explains that the ion storm was so bad he had to jettison a pod with Finney in it … The pod is something new, never seen, never mentioned before and never again. It was a Mankiewicz idea conjured while the starship’s technical capabilities were still somewhat fuzzy.

Finney’s daughter Jame enters to accuse Kirk of murdering his supposed friend. In the various script revisions, Jame was originally a male named after James Kirk. How is it that Jame came to be at Starbase 11? That’s never explained.

Spock arrives with the 23rd Century equivalent of a floppy disk, which he gives to Stone. The data contradict Kirk’s written deposition that he jettisoned the pod after going to red alert; the record shows he jettisoned before. Stone orders Kirk confined to base pending a possible court martial.

After the title credits, there’s a scene in the starbase bar where two other starship officers question Kirk about Finney’s death. Cushman wrote that this scene had to be restaged because Shatner objected to actor Winston De Lugo (the redshirt officer) being taller than him. The scene was improvised so that De Lugo was now sitting instead of standing. IMDB lists Shatner at 5’9” in height; legend has it that Shatner had a rule requiring all characters except Spock to be equal or lesser in height to him, unless the character was sitting or an alien.

Stone records a formal inquiry with Kirk. The exposition reveals that Finney was an instructor at the academy when Kirk was a midshipman. Jame was named after Jim. Kirk and Finney had a falling out years before when they were both serving on the USS Republic (NCC-1371, if you’re keeping score)4. Finney left open a circuit to “the atomic matter pile,” whatever that is. Another five minutes, and the Republic would have kaboomed.

Kirk assigned Finney to the pod because it was Ben’s turn on the duty roster. He testifies that he ordered yellow alert first and gave Finney time to get out of the pod. The storm became so bad that he had to declare red alert and jettison the pod — with Finney still inside.

It’s unclear to me why the pod needed to be jettisoned. We’re never shown the pod, nor is it explained why it’s necessary to jettison it in an ion storm. I guess we’re supposed to accept it, the way we accept that phasers and transporters work.

In any case, Stone says the data card shows the ship was still at yellow alert when the pod was jettisoned — contradicting Kirk’s testimony. Stone offers Kirk an option — to admit he’s “played out” and accept a ground assignment. “No starship captain has ever stood trial before and I don’t want you to be the first.”5 Kirk refuses. The court martial is on.

(NBC thought I’d be bored by now, but I’m enjoying it.)

Back in the bar, Kirk encounters Areel Shaw, yet another old flame who is now “a lawyer in the judge advocate’s office.” (JAG?!) She recommends Samuel T. Cogley to represent him. Oh, and by the way, Areel will be the prosecutor. No nookie for Jim and Areel tonight.6

Kirk returns to his temporary starbase quarters to find Cogley already there. (No privacy planetside, apparently.) As with Jame, it’s never explained whether Cogley lives at Starbase 11 or arrived from elsewhere. If it were me, I’d be a little suspicious that the prosecutor recommended him as a defense attorney, even if she and I had once nookied. Cogley disdains computers, uses only books. Must be an introvert.

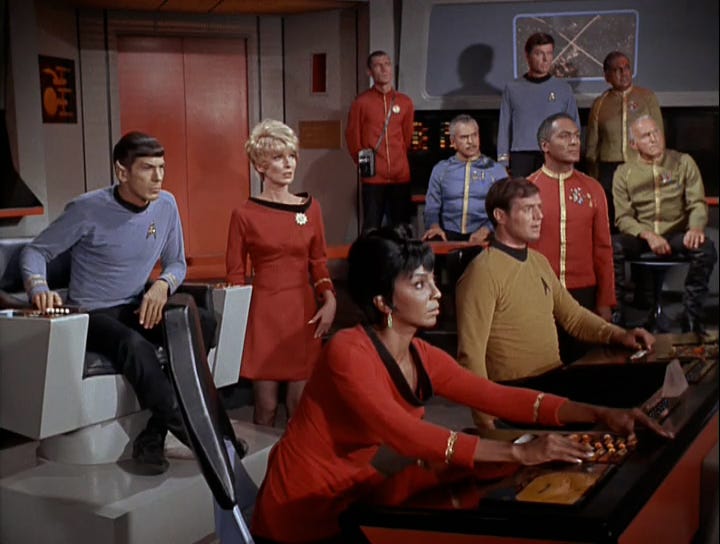

The court martial begins. This episode will become the template for court martials in future Star Trek incarnations.

Cogley fails to question Shaw’s first three witnesses. When Stone asks why, Cogley calls Kirk to the stand. In the middle of the prosecutor’s presentation?! Um, okay. It’s future space law. Anything is possible.

Kirk testifies it was necessary to jettison the “ion pod” to “save my ship — and nothing is more important than my ship.”

We’re still not told the technical reason why the pod had to be jettisoned. Oh well.

JETTISON POD will never be seen again. Perhaps because it was jettisoned?!

The video log shows Kirk pressing the JETTISON POD button on his command chair while still at yellow alert. (Which suggests there’s only one pod. Whatever it is.) “But that’s not the way it happened,” Kirk mutters.

(Sorry NBC, my brain is still engaged with the episode.)

Back on the Enterprise, Spock proves something is wrong with the no-longer-called IRRU. He beats the computer five times at chess, which should be impossible.

This plot point gets the tribunal transferred to the Enterprise, which helps stage the rest of the story and resolve the plot.

Spock argues to the tribunal that his beating the computer is evidence of tampering. Only three crew members were capable of doing so — Kirk, Spock, and Finney. Kirk testifies that a search was conducted after the storm but Finney could not be found. (Nor, presumably, the pod …) Cogley argues that Finney is alive and hiding aboard the ship.

Kirk orders most of the crew ashore. The judges and a few others remain. Kirk proposes increasing auditory sensors by “one to the fourth power.”

Um, 1^4 = 1. Oh well, if the writers were good at math, they’d be mathematicians, not writers.

McCoy uses “a white sound device” to mask the heartbeats of those remaining aboard. Only one heartbeat remains — Finney’s.

The heartbeat is localized to “B deck,” near Engineering. Decks are normally numbered, so this is an inconsistency. Kirk declares “This is my problem” and goes to confront Finney alone. You’d think he’d want witnesses and backup. Another oh well.

With most of the crew ashore, Uhura once again serves at Navigation.

Finney has sabotaged the engines, so the ship is falling into the atmosphere. When Kirk tells him that Jame is aboard, Finney is distracted, so NBC gets the fistfight it wanted. Kirk knocks him out, then repairs the damage. Ship saved. Plot resolved.

Fin. Not to be confused with Finney.

Despite its flaws, “Court Martial” is still a memorable and noteworthy episode. It could have been slimmed even more, e.g. the Jame character serves little purpose other than to upset Finney when he realizes she’s aboard the ship he doomed.

Lexicon notes …

Several times in this episode, the word “Vulcanian” is used to describe someone or something with Vulcan. Eventually the simpler term “Vulcan” will come into favor.

For the first time, the word “Starfleet” is used. McCoy was “decorated by Starfleet surgeons.”

Marc Cushman, These Are The Voyages: Season One (San Diego: Jacobs/Brown Press, 2013), 359.

Joel Engel, Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek (New York: Hyperion, 1994), 90-91.

Are ion storms a thing? Yes, but it’s hard to believe that 23rd Century technology couldn’t handle one. Here’s a 2007 NASA article on solar radiation storms, or “ion storms.” They’re the science fiction equivalent of a tropical storm or hurricane buffeting a ship at sea.

“United Star Ship Republic,“ Kirk states, in case you’re wondering what the USS stands for.

Captain Jonathan Archer of the NX-01 Enterprise stood trial, but that was in a Klingon court.

The Next Generation episode “Measure of a Man” uses a similar plot device. Phillipa Louvois is a JAG lawyer who once prosecuted Picard for the Stargazer loss. (Apparently starship captains can be prosecuted after all.) Louvois in court argues that Data is Starfleet property while Picard defends him, arguing that Data is sentient.