Dagger of the Mind (Episode 11)

As pressures built on him to deliver an action-adventure show on time and on budget, Gene Roddenberry personally rewrote yet another writer's script.

Not who you think it is.

Star Trek was falling behind.

The last two produced episodes had busted the budget and run late in production.

According to Marc Cushman’s These are the Voyages, the per-episode budget was $193,500 (about $1.9 million in today’s dollars) with a six-day production schedule. “Balance of Terror” cost $236,150 to produce (about $2.4 million in today’s dollars) and ran a half-day late. “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” cost $211,061 to produce (about $2.1 million in today’s dollars) and ran two days late.1

The production team was caught in crosswinds blowing from the network and the studio. NBC wanted more action-adventure and scenes on those strange new worlds promoted in the title credits. Desilu wanted the show delivered on budget.

To get his show approved, Gene Roddenberry had promised all this was possible. Although he and his production team were delivering quality episodes, they were under a lot of pressure to keep their promises, or perhaps face cancellation.

The next episode on the production schedule was “Dagger of the Mind.” Shimon Wincelberg was the screenwriter. Wincelberg was in a group of potential writers invited by Roddenberry to attend a March 9, 1966 viewing at Desilu of the second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before.”

Wincelberg was a prolific TV writer, with credits going back to 1953. He occasionally dabbled in science fiction, including six episodes of Lost in Space and one episode of Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea. With creator Irwin Allen, Wincelberg co-wrote the teleplay for the unaired first Lost in Space pilot. He was also credited with co-writing the Time Tunnel premiere episode. Wincelberg seemed a perfect fit for helping Star Trek get off the ground.

According to Cushman, Wincelberg pitched the story of a physician using mind control and torture to heal insane criminals. The title, “Dagger of the Mind,” came from a line in Macbeth.

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?

I see thee yet, in form as palpable

As this which now I draw.

This was one of the first scripts assigned by Roddenberry, but the outline went through five drafts. Roddenberry wrote Wincelberg that the story needed to be simplified, and to focus more on the antagonist than its fantastical science aspects. “There is no possible way to do this tale as presently indicated without going much over budget.”

The fifth draft was shown to NBC executive Stan Robertson, who oversaw Trek’s scripts for the network. Robertson noted that the show was falling into a familiar pattern, with a mad scientist of the week. The prior episode, “What Are Little Girls Made Of,” had Dr. Roger Korby as the mad scientist.

In earlier drafts, yeoman Janice Rand was the crew member who beamed down with Captain Kirk to the penal colony. Stories vary on why Rand was changed to Dr. Helen Noel. Cushman suggests it made more sense for a doctor to operate the neuralizer controls than a yeoman.

But a pattern was starting to emerge — Rand was not in “Little Girls.” (Neither were several other recurring characters.) Under budget pressure, not using Grace Lee Whitney saved a paycheck. The producers were struggling with how to play the unrequited romance between Kirk and Rand; her presence in an episode got in the way of Kirk having liaisons with other women (of which we know there will soon be many).

Roddenberry received several notes from NBC Broadcast Standards asking for certain aspects of the script to be toned down, such as what fantasy Kirk imagines while in the neuralizer, and how he kisses Noel.

Of more importance to Star Trek history is that this episode gave us the Vulcan mind meld. As with many other aspects of the show’s history, a plot point was conceived not from a writer’s brilliance, but from the necessity of complying with a budget constraint or a network directive.

Wincelberg’s script was polished by both Roddenberry and associate producer John D.F. Black. The story had hit a speed bump with a scene in which Spock and McCoy debated how to recover the memories of the impaired Simon Van Gelder. In early drafts, hypnosis was to be used. Spock was to perform the act, but Broadcast Standards objected; McCoy, after all, was the physician, not Spock. Broadcast Standards was leery about depicting hypnosis at all, fearing that a viewer might be hypnotized! In fact, Spock says to McCoy, “It is not hypnosis.” Happy, NBC?2

Both Cushman and, in his autobiography I Am Spock, Leonard Nimoy credit Roddenberry with inventing the mind meld. Cushman wrote that the mind meld “would give Broadcast Standards no reason to fret about unintended effects on home viewers.” In this episode, it was established that the act was dangerous for both the mind-melder and the mind-meldee, but that consequence was forgotten over time.

We’ve discussed in earlier columns that many first season episodes contained elements involving mental powers. Both pilots, “The Cage” and “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” were about mental powers. By the early 1960s, telepathy was a staple of SF writing. My guess is Roddenberry saw this as an opportunity to introduce yet another exotic trait for his resident alien.

As he had with earlier scripts, and as he would continue to do throughout the series, Roddenberry rewrote drafts without the consent of his writers. Wincelberg was so unhappy with the rewrites that he had his screen credit changed to a pseudonym, S. Bar-David.

Production began the afternoon of August 9, after “Little Girls” wrapped up filming in the morning. Once again, the episode would finish behind, but only by a half-day. Unlike the last two episodes, “Dagger” came in under budget, at $182,140 ($1.8 million in today’s dollars).

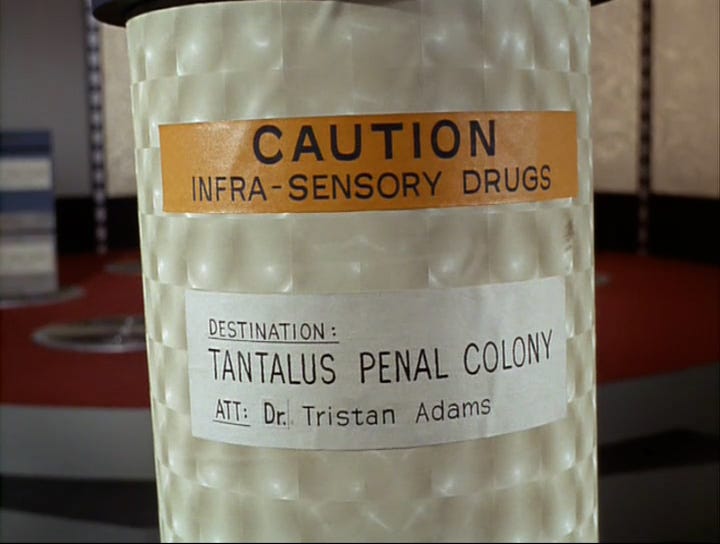

The episode opens with the Enterprise in orbit, but without the usual captain’s log voiceover. We quickly transition to the transporter room, featuring a closeup of a shipping canister with this label:

The 23rd Century version of Amazon Prime.

The primary rule for television writing is show, don’t tell, so this covers a lot of exposition.

The incompetent transporter operator can’t beam down the shipping crates, because he’s forgotten that the penal colony has a security force field. Kirk himself walks in and shows up the redshirt by personally calling the colony to request the shield be lowered.

For good measure, he beams up a crate that’s supposed to contain research materials for the Central Bureau of Penology in Stockholm. (Penology is a thing; click here to look it up.) This box is also labelled in big letters:

CLASSIFIED MATERIAL

DO NOT OPEN

… which works well for the person hiding inside. Kirk suggests the transporter operator revisit the manual on penal colony security procedures, but Kirk himself was standing right there when the crate was beamed up without scanning its contents. In any case, the operator leaves to find storage, leaving a lone technician.

By the way, the box label states that Stockholm is now in EURASIA - NE. Apparently, unlike penology, Sweden is no longer a thing — no specification that this Stockholm is on Earth; as I’ve noted in earlier articles, the Enterprise is established as an Earth ship. We’ve yet to hear the terms “Federation” and “Starfleet.” Spock is the only non-human aboard.

A crazed man, whom we later learn is Simon Van Gelder, emerges from the crate and delivers a judo chop to the back of the neck of the technician, whose back is to the transporter pad. Security truly is lax on the Enterprise these days.

After the title credits, we have our first captain’s log. The Enterprise departed Tantalus V without anyone going ashore. Kirk laments to McCoy that he couldn’t have seen Adams’ operations. “They’re more like resort colonies now.”

The colony calls to say a violent inmate is missing. Kirk orders a security alert. Van Gelder applies a chokehold to a redshirt, disarming the man of his phaser. Like I said, security really is bad on the ship today.

Spock and McCoy exchange a bit of dialogue that doesn’t serve the plot but does expand this fledgling universe. Spock comments that “you Earth people” glorify organized violence but lock up the individually violent. When McCoy challenges him, Spock explains that his people “disposed of emotion. Where there’s no emotion, there’s no motive for violence.” That’s bollocks, of course, but it’s a matter for future episodes.

What happens when you turn your back on the one thing you’re supposed to guard.

Van Gelder reaches the bridge, and judo chops the security officer who had his back to the turbolift. Jeez, these people are bad at their jobs. Didn’t anyone think to disable the turbolifts to keep Van Gelder from moving around? But the plot demands that Van Gelder get to Kirk to drive the story, so here we are. Spock delivers the nerve pinch, invented six episodes earlier for “The Enemy Within.” The nerve pinch was improvised on that set by Leonard Nimoy; Roddenberry must have liked it, because Spock uses it again here. Van Gelder is taken to sickbay; Kirk orders the Enterprise to return to Tantalus V.

Morgan Woodward delivers quite the performance as the psychotic Simon Van Gelder. Most of his acting career was spent playing cowboys, but this episode was a chance to show what he could do. He’ll return as Captain Tracey in the second season episode, “The Omega Glory.”

Nichelle Nichols chews her scene.

Spock discovers that Van Gelder was not committed, but assigned to the facility as Adams’ associate. Kirk orders Uhura to call the penal colony. As Kirk talks to Adams via subspace radio (although it isn’t called that yet), watch Nichelle Nichols in the background. She has no lines, but she certainly plays the part of a communications officer. Nichelle chews on her stylus while listening to the transmissions. As Kirk presses on and off the HOLD button on his command chair, Nichelle is pressing buttons on her console, suggesting Kirk’s button is a signal to the communications officer to open and close the channel. A nice bit of business by Nichelle to sell the importance of her character.

Kirk records a captain’s log using a tricorder. That’s normally the yeoman’s job, but Rand isn’t in this episode, so he hands the device to a redshirt. Um, okay.

McCoy assigns a psychiatrist, Dr. Helen Noel, to accompany Kirk to the colony. Apparently Kirk doesn’t realize she’s the same Helen Noel with whom he once had a dalliance at the Enterprise science lab Christmas party. (Apparently they still celebrate the Earth religious holiday.) It seems implausible that he wouldn’t remember her, since he should know of all 430 crew members. But originally she was supposed to be Janice Rand, so the logic of the scene may have been lost in Roddenberry rewriting Wincelberg.

As the Tantalus elevator rapidly descends below the surface to the penal colony, Kirk and Noel fall into each other’s arms. This harkens back to a scene in “Balance of Terror” where Kirk and Rand embrace as a Romulan torpedo is about to hit the Enterprise. After the first season, Dorothy Fontana will produce a writers guide that frowns on such intimacies as unrealistic. This might have been yet another residue of the replacement of Rand with Noel.

The first Vulcan mind meld.

The mind-meld scene in sickbay is largely exposition to deepen the mystery of Tantulus Colony. I can’t help but admire the acting by Woodward and Nimoy. I wish I could have watched them plan out acting this scene. In his autobiography, Nimoy wrote that “it gave me an opportunity to emphasize the importance of touch to Vulcans; Spock uses his finger and hands to ‘probe’ Van Gelder’s face and skull.” Nimoy found it “a far more dramatic way to extract information than a lot of questions.”

In yet another contrivance, Kirk decides to sit in the neural neuralizer with Noel operating the controls. Recklessness eventually becomes one of Kirk’s traits, but nonetheless one has to question the wisdom of the act. Adams and his mind-wiped assistant overpower Noel, so Adams can implant obsessive love for Helen in Kirk’s mind.

What’s the point? If Adams’ objective is to evade suspicion and continue his evil research, then why not just wipe Kirk’s memory and plant false conclusions? Why not do the same with Helen? They would both beam up, file their report, mind-wiped Kirk would order the Enterprise to take Van Gelder to another facility and the universe unfolds as it’s meant to be.

In any case, Kirk sends Noel through an air duct low enough and big enough for humans to crawl through, so she can somehow cut off the power. Another contrivance. Air ducts are just lazy writing, in my opinion. Jeffries tubes will soon become the starship equivalent of the air duct plot device. Two minions take Kirk at phaser point, but no one questions what happened to Noel, perhaps because they’ve been mind-wiped and are now dullards.

Helen finds her way to the power room, opening another air duct screen which swings like a door instead of being screwed down like all the air ducts in my house. Despite having no training in such things, she finds a giant HIGH VOLTAGE ON/OFF lever which she pulls down. Kirk escapes his torment, leaving Adams lying on the floor.

With the security shield disabled, Spock beams down armed with a phaser, followed by McCoy and a security team. For some reason, Spock turns the power back on. Adams had left the neuralizer set at full intensity, so when it reactivates the device wipes his mind. McCoy makes it official — “He’s dead, captain.”

Van Gelder returns to the colony to destroy the neuralizer. It seems to me that McCoy and Noel could have safely used it to deprogram Kirk of his Helen obsession, but instead we’re left with a note about the loneliness of command.

Fin.

I write off this script’s weaknesses to the crosswinds. Roddenberry needed to get his starship back on course. That meant running roughshod over his writers, actors, staff, whatever it took. It’s watchable thanks to the acting performances by the entire cast, as well as the production values.

The next episode to be produced will be “Miri.” It was during that episode that Grace Lee Whitney was sexually assaulted by someone she described in her autobiography as an “executive.” She was dismissed from the show shortly thereafter. Was it Roddenberry? Grace never said, but we’ll explore the evidence in our next article.

The cost in current dollars is calculated by using the original dollars as reported in Marc Cushman’s These are the Voyages and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CPI Inflation Calculator.

In Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry, author David Alexander cites on page 242 a May 2, 1966 memo from Roddenberry to his writers detailing Spock’s character and background. “Hypnotism is an everyday tool on Spock’s home planet, deriving from the intellectual intensity of the culture there. He has this capacity — and when we play it, we stay accurate, never get into hypnotism-fantasy.” According to Marc Cushman, Shimon Wincelberg submitted his fourth revised story outline on May 9. That might explain why Spock was written to perform the hypnotism. By the way, Roddenberry wrote that on Spock’s home world hypnosis was “part of the sex act” which had “a somewhat more violent quality” than on Earth. Yikes.