Miri (Episode 12)

Grace Lee Whitney was sexually assaulted while filming this episode, then was told her contract would not be renewed.

Grace Lee Whitney filmed this scene after she was sexually assaulted by an unnamed executive.

Crew Rotation

Star Trek exhausted Gene Roddenbbery.

It exhausted his associate producers too, Bob Justman and John D.F. Black. Justman took care of daily production, while Black supervised the scripts.

The show was behind schedule and over budget.1 The special effects, of a sophistication never attempted for weekly television, had not yet been delivered.

“Miri” was scheduled to begin production on August 22. Adrian Spies was a veteran television writer who had written six episodes for Desilu Playhouse, including one for Desi Arnaz himself. But Spies had no real science fiction experience.

In March 1966, Spies pitched to Roddenberry his idea about an Earth-like world populated by children who were actually very old. As with many of Star Trek’s early scripts, this one’s delivery dragged out too, buffeted by Justman’s requests for rewrites to reduce costs, Black’s draft polishes, and Roddenberry’s tinkering with the script as he had with others.

By early August, Star Trek needed help. Roddenberry hired Gene Coon, another veteran TV writer who’d recently served as a producer and story editor at The Wild Wild West. John D.F. Black was on his way out2; he asked Roddenberry not to renew his contract, so Coon and Black had some overlap time for Coon to become familiar with the show. On his way out the door, Black collaborated with Roddenberry and Justman to write the show’s famous opening narrative, “Space, the final frontier …”3

Coon’s first assignment was “Miri.” According to Marc Cushman, “Coon’s rewrite is a prime example of small changes making big differences.” In the last days before principal photography began, Coon circulated final drafts with Roddenberry, Justman, and NBC.

“Miri” was the first Star Trek episode to be shot on location. The exterior scenes were shot at Desilu’s Culver City lot. The location is one of the most historic in the film industry, going back to 1916. It was here that the giant gates swung open in the 1933 movie King Kong; those gates were destroyed as Atlanta burned for Gone with the Wind. The first Star Trek pilot, “The Cage,” filmed on this lot. During the 1960s, it was used by Hogan’s Heroes and The Andy Griffith Show.

This 2020 MeTV video shows Desilu-Culver locations shared by “Star Trek” and “The Andy Griffith Show. Video source: MeTV YouTube channel.

Amazing Grace

This would be the last episode with Grace Lee Whitney’s Janice Rand in a featured role. Although sources vary on the reason, for years the consensus was production costs. Her contract had guaranteed only seven episodes; the yeoman could be portrayed by any actor paid less to perform the character.

That was the public story until Grace published her biography in 1998, The Longest Trek: My Tour of the Galaxy.4 Whitney revealed that an executive had sexually assaulted her during the filming of “Miri.”

Who was the executive? Grace declined to name her assailant, writing that it wasn’t her place to expose him. Some believe that the evidence points to Roddenberry. Gene is the most likely in a limited pool of suspects.

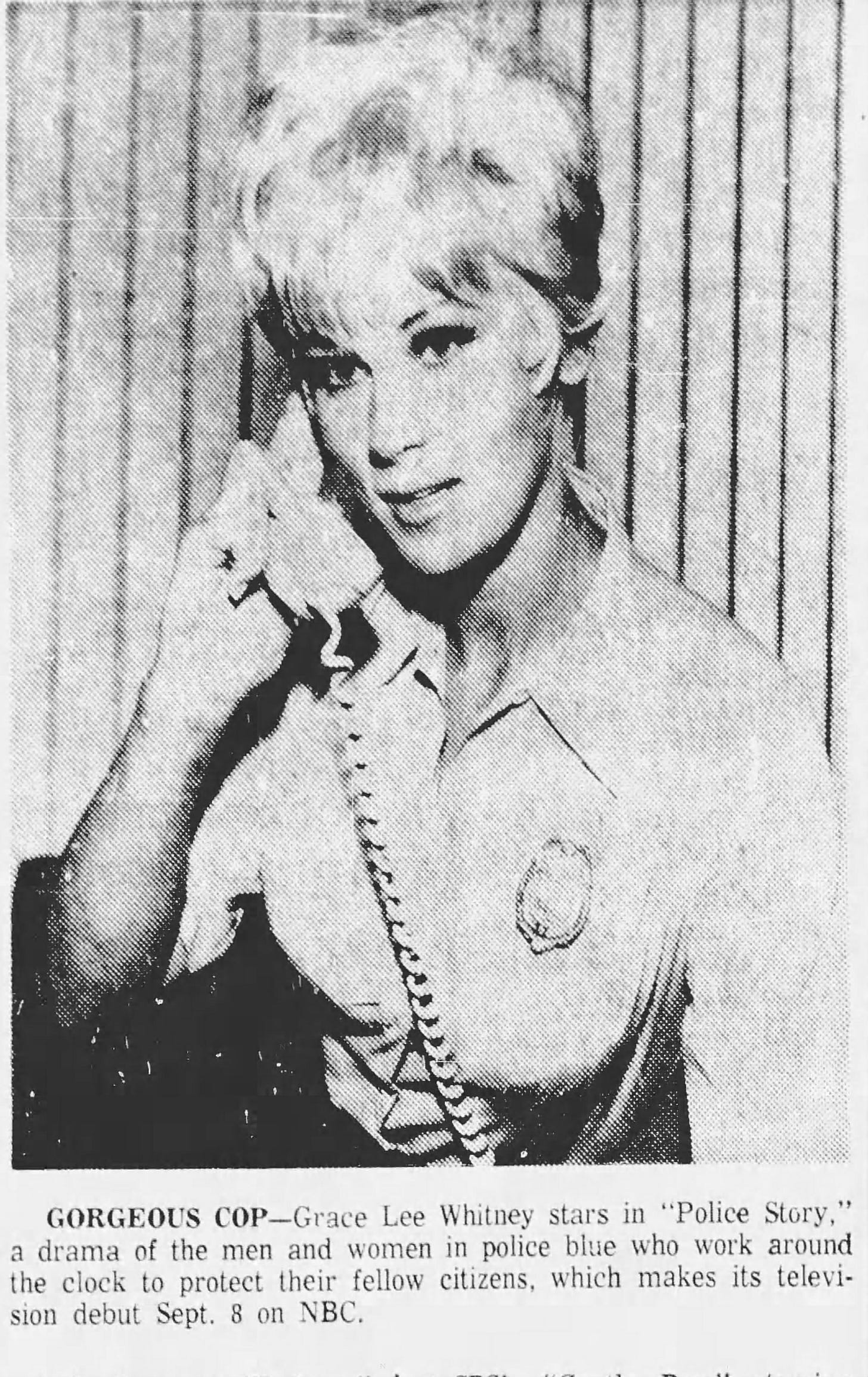

A publicity photo of Grace Lee Whitney as she appeared in the pilot for the proposed “Police Story” series. Image source: The Durham Sun, August 22, 1967, via Newspapers.com.

Whitney wrote that she met Roddenberry when he cast her for a pilot called Police Story. After that failed to sell, he requested her for the role of Janice Rand. She drove down to Desilu to meet with him, where he described the yeoman as “the object of [the captain’s] repressed desire.” Viewing the opportunity as regular employment on a weekly series, Grace signed the contract in April 1966.

In her book, Whitney wrote that the assault occurred on Friday evening, August 26, 1966, after filming on the episode “Miri” wrapped for the week. Alcoholic drinks were served on the set. The executive then offered to escort her to an empty office to discuss her future on the show. He was an executive she trusted; Grace wrote that she’d known the man for “a couple years” and that he was known as a womanizer but not a monster.

In the office, the executive plied her with more alcohol. He asked her to role-play Kirk and Rand with him, directing that Rand had a repressed desire and hunger for sex with Kirk. Grace described him as someone who “had a lot of power over my future.” When he asked her to undress, she refused, and reminded him of his relationship with another woman. He replied, “She doesn’t care,” that she was aware of his affairs with other women. He blocked her exit and began to undress himself. “He had the power to destroy my career and we both knew it.” As he forced her to perform oral sex on him, she believed that her employment at Star Trek was at an end.

Grace confided in Leonard Nimoy that night what happened, but Leonard didn’t discuss it in his autobiography. The principals — Whitney, Roddenberry, Nimoy — are all deceased so, unless someone one day produces evidence, we’ll never know for sure. Grace wrote in a chapter titled “Great Bird of the Galaxy” about her relationship with Gene, calling them “two sides of the same coin.” Both had their demons. She forgave him for dropping her character, especially when she was invited back for The Motion Picture. There’s no evidence in this chapter to suggest he was the one who violated her.

Grace Lee Whitney as Janice Rand in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.” Image source: Memory Alpha.

The clue pointing to Roddenberry as the assailant is Grace’s recounting of what happened when she reported to work the Monday morning after the assault. While she and Nimoy were in the makeup trailer, the executive came in and gave her “a polished gray stone.”

Several Star Trek history books document that Roddenberry polished stones as a hobby. Joel Engel wrote in his 1994 unauthorized Roddenberry biography that John D.F. Black “shared rock-cutting as a hobby with Roddenberry and Alden Schwimmer,” Roddenberry’s agent.5 In his autobiography, Leonard Nimoy wrote that “Gene and Majel were avid gemologists; they bought unfinished gemstones and polished them, then resold them.”6

By August 26, Black had left the show. Schwimmer was an agent, so he wouldn’t be someone in a position to write the Rand character, much less being on the set for a Friday night party or walking into the makeup trailer. That leaves Roddenberry. As we’ve discussed in earlier articles, Roddenberry had a reputation as a womanizer. At the time of the assault, he was having an affair with Majel Barrett while still married to his first wife, and at one time had an affair with Nichelle Nichols.

Grace wrote in her 1998 memoir, “Today, the Executive can no longer hurt me.” Roddenberry passed away in 1991. Was that another clue? We’ll never know.

Whitney wrote that she never had a “romantic relationship” with Roddenberry, but that he made, “Passes, innuendoes, double-entendres, the whole nine yards.” She commented, “Who knows? Maybe if Gene had gotten me in the sack, I might have done all three seasons of Star Trek instead of only half a season!”

After filming the episode, her agent informed her that she’d been written out of the show. (This was during a two-week hiatus between “Miri” and “Conscience of the King.”) According to the agent, he’d been told that Rand was too close to Kirk, that they wanted the captain to have relationships with other women.

In their memoir, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, Herb Solow and Bob Justman wrote that in early September 1966 Roddenberry proposed dropping the Rand character to Desilu executives. They speculated this was due to her weight gain and substance abuse. Solow found it odd that Roddenberry wanted her gone, because until this time Gene had fiercely defended the character. Solow wrote that there were rumors of “a sudden personal rift between Gene and Grace that occurred just prior to her departure from the show.”7 This book was published two years before the Whitney bio, so they may have been unaware of the alleged assault.

Star Trek Creator, Roddenberry’s authorized biography by David Alexander, cites internal memos from the time as proving her departure was strictly financial. Alexander references an internal memo from a consultant who concluded that Whitney was underused. “Grace for the most part has cost us a lot of money for the little that we use her in each show.” His recommendation was to replace her with “a free lance player” who would be paid less. A memo was sent September 8, 1966 from Desilu Business Affairs to Legal directing that Whitney’s agent be informed that her contract was being terminated. Alexander concludes, “the real reason Grace Lee Whitney left the show was financial.”8

“Miri” in my opinion is Whitney’s best work with Star Trek. She had to show a range of emotions that would have challenged any actor. Her performance had to be colored by Rand’s love for Captain Kirk, unrequited by duty and rank.

Let’s explore her final featured performance.

This Looks Familiar

Haven’t we met?

Gene Roddenberry’s March 11, 1964 series pitch “STAR TREK is …” had promised that our starship (then called the SS Yorktown) would visit “worlds ‘similar’ to our own.”

The “Parallel Worlds” concept is key to the STAR TREK format. It means simply that our stories deal with plant and animal life, plus people, quite similar to that on earth. Social evolution will also have interesting points of similarity with ours.

Roddenberry wrote that the Parallel Worlds concept not only meant locations familiar to a general audience, but production would be affordable with “earth” casting, sets, locations, costuming, etc.

“Miri” is the first of several episodes to take the parallel Earth concept literally. An “earth-style” SOS is detected transmitting from a duplicate Earth — one without any weather systems, apparently, because we see no clouds anywhere on the planet. (The consequence of a limited effects budget.)

The Mayberry Courthouse with Floyd’s Barber Shop to the left. Image source: Retroweb.com.

Return to Mayberry. The courthouse columns can be seen behind the landing party.

Kirk leads a landing party of six — Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Rand, and two expendable redshirts. Let’s see if they survive the episode.

Spock estimates that this is a duplicate of Earth circa 1960, fulfilling Roddenberry’s promise to visit worlds familiar to a general audience. The distress signal apparently was sent centuries ago.

Out of nowwhere, a zombie creature attacks McCoy. Kirk delivers three punches to the zombie, although Spock at one point holds the creature and could have used his nerve pinch. Oh well. The zombie sniffles and whimpers like a child. The creature dies; McCoy delivers the line, “It’s dead.” The doctor scans the deceased and finds that it aged a century in just a few minutes.

Inside one of the buildings, the landing party finds a pre-teen girl named Miri. She begs the adults not to harm her. She tells of “grupps” who destroyed the planet (a term we later discover means “grownups.”) McCoy deduces that the grupps died from a plague.

Kirk turns on the charm hoping to coax Miri into cooperating, but it has the unintended consequence of her developing a crush on the captain. That’s an emerging trope we’ll see time and again throughout the series — love ‘em and leave ‘em. It’s a bit creepy here, since the girl is pre-pubescent. (Kim Darby, who plays Miri, was 19 at the time of filming.)

Out on patrol, Spock and the two redshirts are ambushed by feral children. They’re pretty much harmless, but the landing party points phasers at them anyway.

Kirk touches Miri and develops a blister on his hand. The splotches soon appear on the other landing party crew members, except for Spock. Miri leads them to a building with a laboratory and the SOS transmitter. Old documents reveal the plague was a failed experiment to prolong human life. Spock deduces that the disease may be linked to the onset of puberty.

Using the starship’s computers, the calculation is that the landing party has about a week left before they die from the plague. This is a very old instrument in a writer’s tool kit - setting a ticking clock. The clock has started.

Exploiting her crush and taking her by the hand, Kirk asks Miri to introduce him to the other children. Several of them are played by the children of cast members, including Shatner and Whitney. Roddenberry’s two daughters were in the group, as well as director Vincent McEveety’s nephew. They scatter when another zombie appears.

Led by an older child named Jahn, the children plot to steal the landing party’s communicators. While the children create a distraction, Jahn sneaks into the lab through the always-handy air vent, then steals the communicators. Five of them. This seems to me to be a weak point in the plot; would you run off without your cell phone just because you heard some children chanting? Not one of them thought to grab a communicator? And where are the security redshirts? This one is on the captain. (Actually, it’s on the writers.)

Suppose you’re in command of the Enterprise. Communications have suddenly ceased. You’ve been ordered by the captain not to beam down any more crew members. But that doesn’t mean you can’t beam down more equipment. Why not send down another communicator to see what happens? You’ve probably been beaming down meals, so why not send a message asking if the landing party is okay? If not, instruct that you’ll be sending another communicator. This is the building from which the SOS was transmitted. Can’t the landing party use the transmitter to contact the Enterprise? Another goof.

This has always bugged me about the general premise of a landing party. Why send down humans when you could send down a drone or robot? The answer, of course, is there would be no tension in the story if our heroes are not at risk. And on a 1960s TV show budget, building drones probably wasn’t affordable.

Kirk records in his log that the children’s food supply is running low. The children had a 300-year supply of edibles?! Seems rather implausible. Setting another clock.

Tempers begin to flare. Rand snaps and runs out the lab into a corridor. She tells Kirk, “ I used to try to get you to look at my legs.” Janice begs him to look at her infected legs. I have to wonder if this was a Roddenberry tinker, because he often was the one who added a bit more sexual tension to a scene. Miri sees Kirk hug Rand; driven by jealousy, she returns to Jahn and proposes kidnapping Janice as a trap for the captain.

Showing signs of the plague, Miri leads Kirk to where the children have Janice tied up. (No security officers accompany the captain; in fact, we haven’t seen them for quite some time. It’s like exposing the king on the chessboard.) In a terrifying scene staged by director Vincent McEveety, Kirk is surrounded by the children, who club him with a hammer and other weapons. The scene seems to borrow from Piggy’s death in the 1954 William Golding novel, Lord of the Flies. Marc Cushman commented that Golding “was clearly borrowing from other sources. Consider this William Golding’s Lord of the Flies meets Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, in search of the Fountain of Youth.”

Piggy is murdered in the 1990 film version of “Lord of the Flies.” Video source: Movieclips YouTube channel.

Unlike Piggy, Kirk survives his beating. While he pleads for their cooperation, Spock leaves the lab to check on his progress. Left alone, McCoy injects himself with a possible antidote, not knowing the proper dosage. Kirk arrives with the children and the communicators. Needless to say, the antidote works.

William Shatner returns to the lab carrying his daughter Lisabeth.9

Back on the bridge, McCoy and Rand stand next to the captain’s chair. Kirk says he’s contacted “Space Central” to request teachers and advisors. (Starfleet Command still doesn’t exist as a term.) The captain orders Spock to take the Enterprise to warp, and off we go to the next adventure.

In the end credits, DeForest Kelley and Grace Lee Whitney appear under “Featuring.” Roddenberry’s original vision for the show was a core character group of four — Kirk, Spock, McCoy, and Rand. After the two-week hiatus, Kelley was signed to a new contract, while Whitney was let go.

It’s a shame we never saw Rand other than a glorified clerical assistant. If the role was considered superfluous, she could have been reassigned to navigation, a position not held by a regular cast member until Walter Koenig arrived in Season Two to play Chekov. What might have been, for Janice and for Grace, if not for a Friday night in a Desilu office building.

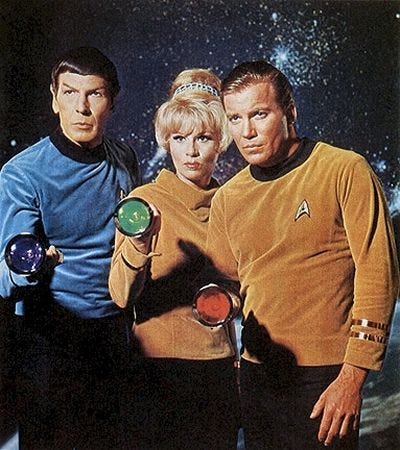

A 1966 publicity image featuring Kirk, Spock, and Rand. Image source: Flickr.

P.S. The two redshirts survived, although they disappeared for much of the episode.

As recounted by Marc Cushman in These Are The Voyages: TOS Season One (San Diego: Jacobs/Brown Press, 2013), 298-314.

Herbert F. Solow and Robert H. Justman, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story (New York: Pocket Books, 1996), 139. Justman wrote that Black was upset about Roddenberry constantly rewriting other writers’ scripts, as well as his own. (This led to complaints being filed with the Writers Guild of America.) “On the day his contract expired, he and [his secretary] Mary Stilwell opened a bottle of champagne in his office and, toasting the occasion, celebrated the fact that he no longer worked for Gene Roddenberry.”

Cushman, 301.

Grace Lee Whitney with Jim Denney, The Longest Trek: My Tour of the Galaxy (Sanger, California: Quill Driver Books, 1998). The book is available on Google Books at this link.

Joel Engel, Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek (New York: Hyperion, 1994), 98.

Leonard Nimoy, I Am Spock (New York: Hyperion, 1995), 101.

Solow and Justman, 243-244.

David Alexander, Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry (New York: Penguin Books, 1994), 254-255.

Lisabeth Shatner, Captain’s Log: William Shatner’s Personal Account of the Making of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (New York: Pocket Books, 1989), 13.